The announcement by presidential candidates Raila Odinga of Azimio and George Wajackoyah of the Roots Party that they will boycott today’s presidential debate has elicited mixed reactions, with questions raised about the debate’s importance.

While the organizers argue that the debate is “for the people, not the candidates,” civil society has criticized Raila and Wajackoya’s decision.

According to Clifford Machoka, the Head of the Presidential Debate Secretariat, such a discourse provides an opportunity for Kenyans to engage in issue-based politics, as opposed to political rallies, which many voters do not attend.

“In a country with diverse voices, debate clarifies issues beyond what we see in campaigns.” “It allows voters to make informed decisions and holds leaders accountable for what they say,” Machoka said.

In Kenya, formal political debates are nothing new. Kenyans witnessed the first two-round presidential debate on February 10, 2013, followed by the second two weeks later.

It was the first political discourse of its kind, freeing politicians from the “us versus them” rhetoric that was usually laced with mockery and political slurs aimed at their opponents, and creating a space where politicians could speak directly to the electorate about issues that were bothering them.

All eight candidates participated in the 2013 presidential debate, where they discussed land issues, foreign policy, and the economy.

It was the first political discourse of its kind, freeing politicians from the “us versus them” rhetoric that was usually laced with mockery and political slurs aimed at their opponents, and creating a space where politicians could speak directly to the electorate about issues that were bothering them.

All eight candidates participated in the 2013 presidential debate, where they discussed land issues, foreign policy, and the economy.

Uhuru was pressed to reveal how many acres of land the Kenyatta family owns and how, if elected, he would address the land issue fairly.

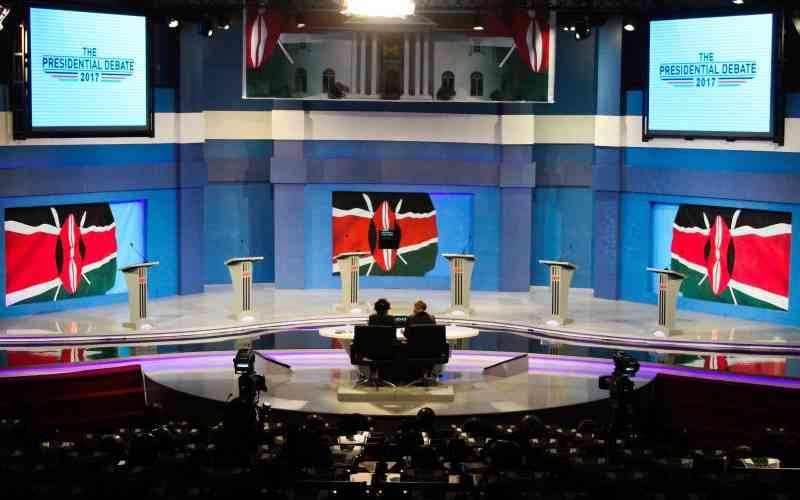

In 2017, President Kenyatta chose to avoid the debate between himself and Raila.

In today’s discussion Raila Odinga Presidential Campaign Secretariat Spokesman Makau Mutua stated that the Azimio la Umoja One Kenya flagbearer would not participate in a process that he claimed his opponent William Ruto tried to influence to be free of corruption and integrity questions.

“He is a man who cares nothing about ethics, public morals, or shame.” That is why, according to Prof Mutua, “we do not intend to share a national podium with someone who lacks basic decency.”

Prof Wajackoyah, on the other hand, believes that dividing aspirants into two tiers is biased and serves to isolate some candidates.

Mr Irungu stated that the presence of all presidential candidates arguing out issues on one stage and in a civilized manner is a statement of a mature democracy, and that any candidate withdrawing at this stage is unwise.

“This Presidential Debate is not a political duel, nor is it a televised debate watched by 34 million people.” These debates are how we, as voters, hear all ideas and select those who will lead us.

“They are the starting point for rebuilding national public accountability and all candidates’ leadership integrity,” he said.

The debate has also grown significantly, which is seen as a sign of a mature democracy. In comparison to the debates in 2013 and 2017, this year’s discussion expanded to include presidential running mates and a Nairobi governor candidates’ debate, all of which were well received.

“The debates allow us to shift away from the rally format and elevate the conversation.” This allows the audience to compare the aspirants’ submissions,” said Irene Kimani, a member of the Presidential Debate Secretariat.

Unlike the 2013 debates, which featured all eight presidential candidates on the same stage for a three-and-a-half-hour marathon, this year’s regulations, like those in 2017, divided the debate into two tiers based on the candidates’ popularity as determined by recent opinion polls.

Those who scored less than 5% will be separated from those who scored higher.

Despite receiving overwhelming praise for its first execution in 2013, there was criticism of having all candidates debate at once, with many saying it was too cumbersome and difficult to follow.

“We chose this format because it allows us to delve deeper into issues and gives each candidate enough time to address them,” Ms Kimani explained.